What is climate change exactly, and why is it happening?

The long-term average weather of a certain location, the repetition of weather patterns over years or decades, is referred to as climate. As a result, it is critical to never infer climate change from a single point in time. As climate change processes have occurred on a frequent basis in the past, entirely rewriting the functioning of natural systems, the Earth’s climate is constantly changing on its own, without human influence. Normally, these processes take hundreds or thousands of years. As confirmed by the latest IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the most important and authoritative body dealing with climate change) report, the sixth, due in 2021, which was prepared after reviewing tens of thousands of papers and involving thousands of experts, the drastic climate change we are experiencing today is a highly accelerated, unnatural process that is demonstrably the result of human activity. If you look at the statistics, you will see that the frequency of extreme weather occurrences has substantially increased in the short term, which is also a result of how human activities are affecting the climate.

Why should we be concerned about climate change? – impacts and consequences

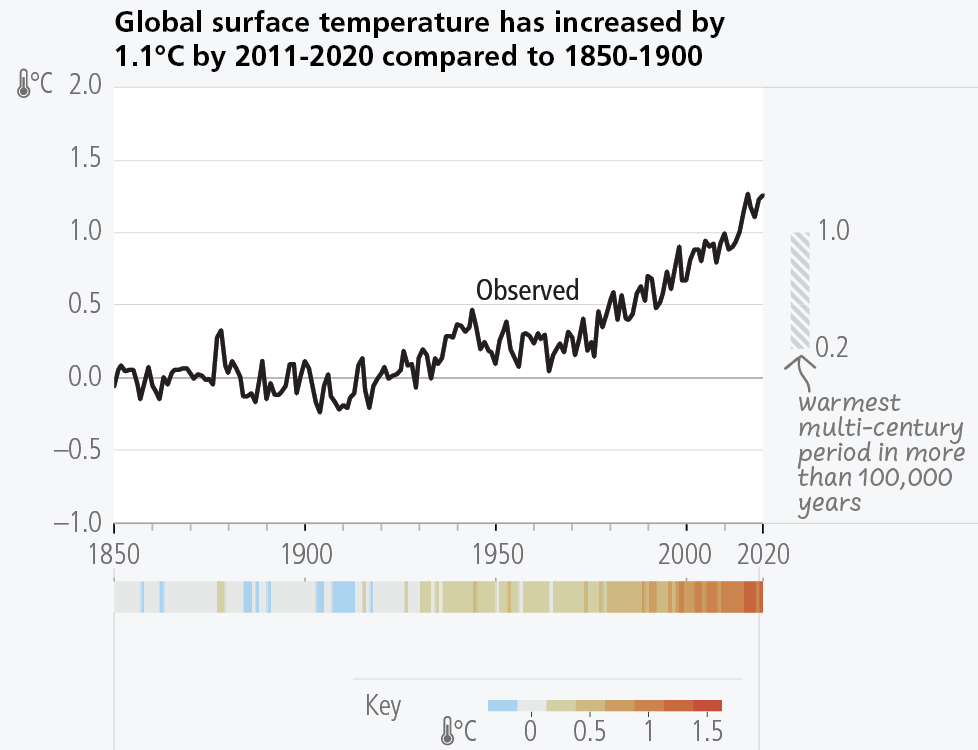

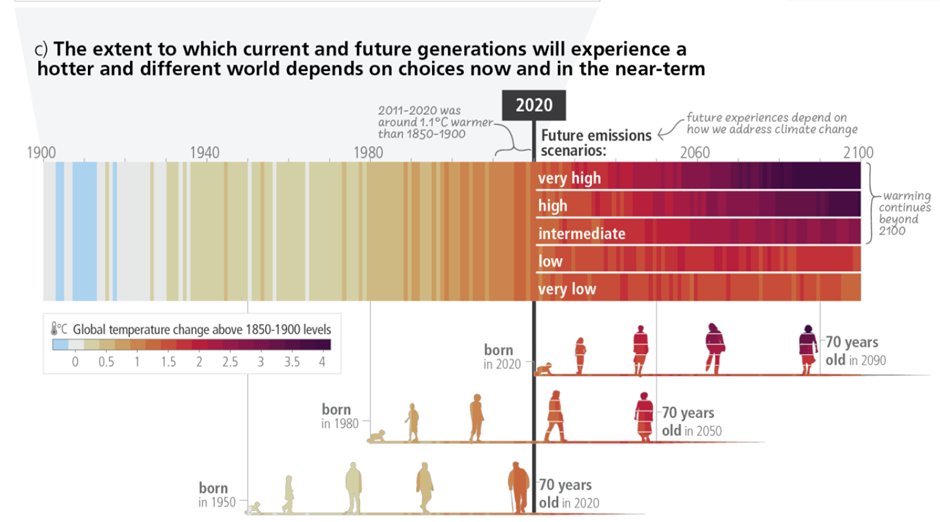

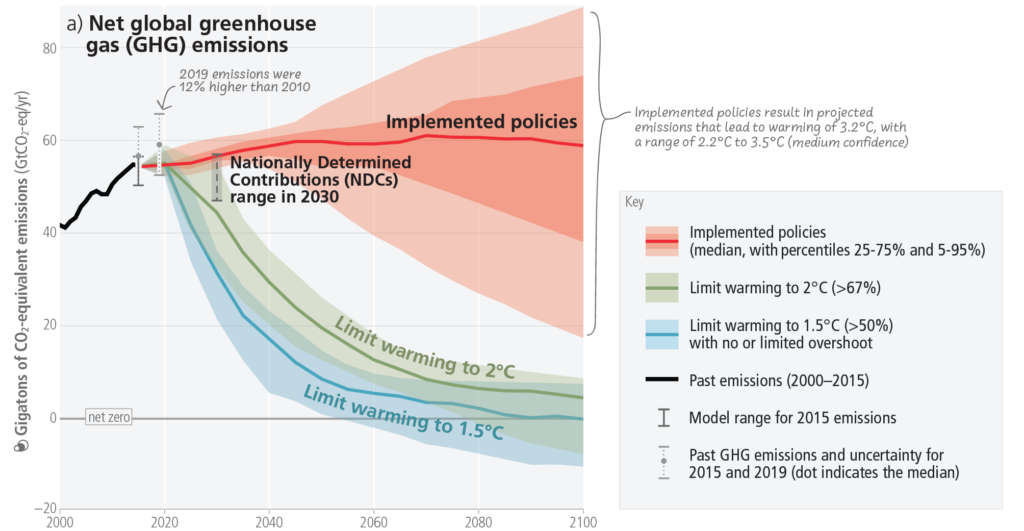

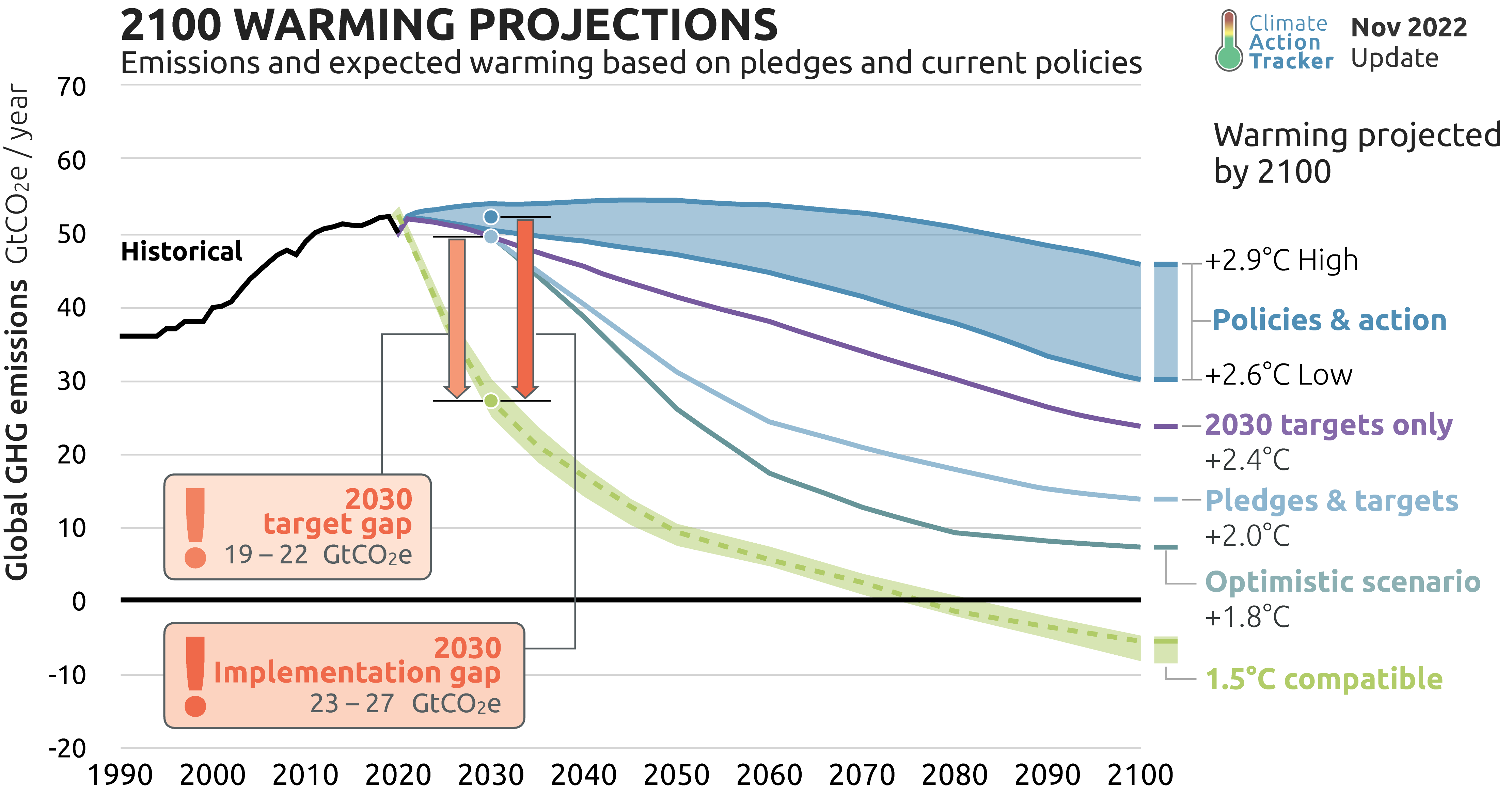

By 2020, the Earth’s average temperature became 1.1°C warmer than it was before the Industrial Revolution. If current emission trends continue, the rate of warming will surpass 1.5°C between 2030 and 2050. Given that the IPCC has determined that 1.5°C is the essential level to which society and wildlife can still adapt, keeping warming well below 2°C and striving for 1.5°C are crucial. In order to halt climate change at this rate, greenhouse gas emissions must begin a sharp reduction within two to three years and reach zero by the year 2050. All facets of the economy and society, including industry, agriculture, energy production, transportation, and consumption patterns, will need to be drastically changed in order to accomplish this.

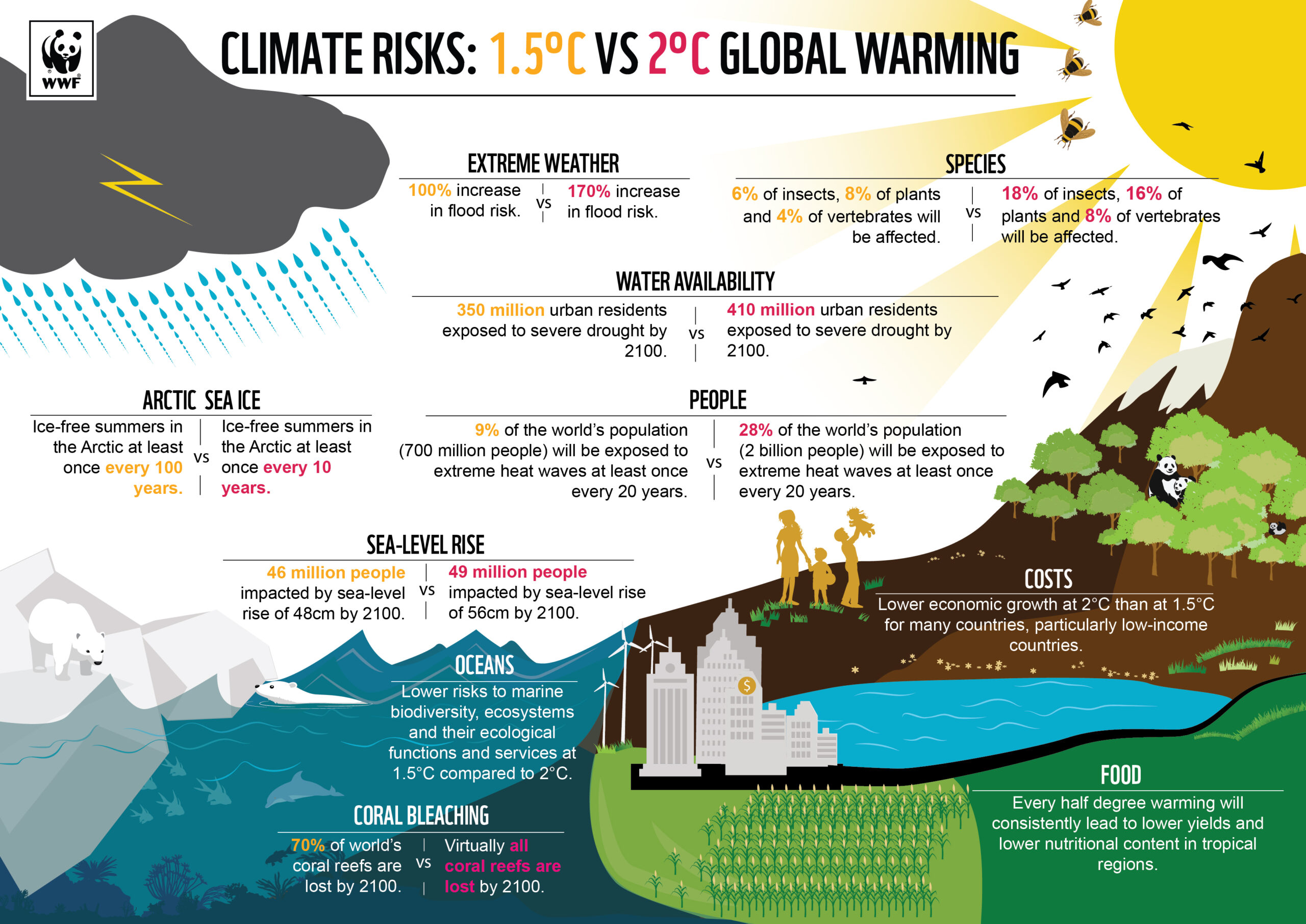

Climate change will have serious effects and implications on natural systems and socioeconomic systems worldwide, including in Hungary, if we do not take the necessary steps. Only a quarter of coral reefs, for example, will survive even at 1.5°C of warming and nearly none at 2°C. Biodiversity is decreasing, species are vanishing, and there are less and fewer of them. The effects on people include heat-related fatalities, increased summertime pollution and its negative health effects, and the migration of infectious diseases typical of tropical regions to higher latitudes. By 2050, it is predicted that approximately 140 million people will be compelled to leave their home countries as a result of climate change. We anticipate changes in our nation’s average annual river run-off, precipitation distribution throughout the year, frequency of flash floods, and infiltration rates, among other things. Groundwater quality is getting worse, and inland floods are happening more frequently and more violently. Erosion dramatically lowers the amount of organic matter in the soil.

Who is responsible for climate change?

Our collective usage of energy is to blame for about two thirds of the emissions that result from it. We use energy directly by using electricity, burning fuel, and heating or cooling our buildings for comfort, but we also use energy indirectly by using it to generate the food and goods we purchase. These are mostly met by oil, gas, and coal.

Climate change is not being contributed to evenly by all countries. In 2021, five nations and the European Union accounted for around two-thirds of global emissions (China 31%, US 13%, EU 8%, India 7%, Russia 5%, Japan 3%). The richest 10% of earnings on the planet (with incomes over 600,000 HUF/person/month) are responsible for half of total emissions. Because carbon dioxide can linger in the atmosphere for generations, the cumulative emissions during the last century and a half should be included. For example, the United States and the European Union currently release just around 20% of total emissions in a year, but when previous emissions are considered, they account for about half of all emissions. We utilize the notion of common but differentiated responsibility due to the vast variations in responsibility and financial resources.

What is the solution to climate change?

Emission reduction

To keep warming below 1.5°C, we must cut greenhouse gas emissions (mostly by deploying sustainable, renewable energy sources and reducing our energy use). We must phase out fossil fuels, the primary driver of the climate problem, from our energy systems, as continued usage of the existing energy sources will already exceed 1.5°C. We also know from climate models how much more greenhouse gases we can produce without exceeding a certain temperature, which is referred to as the carbon budget. We have already used up practically all of the remaining greenhouse gas emissions up to the 1.5°C warming limit and one third of them if we look at the 2°C warming limit, assuming that the 2019 emissions level is maintained between 2020 and 2030.

Adaptation

In all fields (such as agriculture, water management, health, building, and urban planning), adaptation to a changing climate is crucial in addition to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Only by working together can these two activities be successful. If we just cut our emissions without adapting, the warming that is already unavoidable would still result in significant harm. Additionally, we will experience a degree of climate change for which we are unprepared if we only adapt and do not reduce our emissions. Nature-based water retention is a key component of our climate change and energy approach; learn more here.

The Paris Agreement and 1.5 degree climate scenarios

Participating countries committed to the 2015 Paris Agreement, to which 195 countries signed up to keep global average temperature increases well below 2°C and to work toward a temperature increase of no more than 1.5°C by 2100. The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was instructed as part of the agreement to investigate the effects of a 1.5°C average temperature increase on the Earth’s ecosystem and to develop a scenario for decreasing greenhouse gas emissions to reach this warming limit.

The report, which involved tens of thousands of researchers, emphasizes that although drastic reductions in greenhouse gas emissions are required, there is still a potential that global warming will stay below 1.5°C. If the trend in emissions continues, humanity will surpass the 1.5°C threshold in less than 20 years. The average temperature increase is currently 1°C above pre-industrial levels. To prevent severe climatic catastrophes, it is imperative to reach this level. According to the report, a 2°C increase would result in much more severe issues than previously predicted: extreme weather events would cause a sharp rise in fatalities, forcing a mass migration from the worst-affected areas; and species extinction rates would be much higher than previously predicted for both plants and animals.

Numerous nations have made voluntary pledges as part of the Paris Agreement, but these are insufficiently aggressive because they only ensure a maximum average temperature increase of 3.5°C. Therefore, it is crucial that nations reevaluate their current climate policies and set goals for lowering greenhouse gas emissions so that mankind can seize the last window of opportunity and avoid leaving a planet that is doomed to extinction for its future generations.

The Climate Policy of the European Union

Due to its large reliance on imported energy, the EU has a financial interest in converting to renewable energy sources and views the sector as a chance for economic growth in the face of international market rivalry. As a result, among the main economic powers, the EU’s climate policy is regarded as being the most ambitious.

At pan-European level, the EU has climate goals for 2030:

- 55% less greenhouse gas emissions compared to 1990 levels

- Increasing the rate of the renewable energy sources to 42.5%

- Energy savings of 11.7[11] % and a gradual increase in average annual savings up to 2030, from 0.8% now to 1.49% in 2024 and 1.9% thereafter – it is important to note that this is not compared to current energy consumption, but to a projected 2030 figure, assuming no additional interventions.

Due to existing differences in energy mix and socioeconomic conditions, the EU does not operate equally throughout Member States; there is some level of national competence. Each Member State pledged goals for renewable energy and energy efficiency in its 2030 Climate and Energy Plan, which had to be completed by the end of 2019 and amended by June 2023. The European Union has committed to achieving complete carbon neutrality by 2050.

The Fit for 55 set of recommendations also revised and implemented a number of EU-level regulations in addition to these state powers. The EU ETS, the EU’s emissions trading system, including aviation within the EU as well as energy-intensive industries, covered 40% of all GHG emissions in 2005. By 2030, emissions from the 2005 base year will have decreased by 62% thanks to the Member States’ emissions trading program. Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) will gradually be implemented in order to preserve the competitiveness of products in the EU that carry a carbon quota price premium. Another significant change is the implementation of the so-called ETS 2, a new emissions trading system for domestic energy usage and transportation, which will go into effect in 2027 or, in the event of high gas prices, in 2028. The package also includes a number of other components, such as changes to the Social Climate Fund, the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive, and the requirements for vehicle emissions. The Renewable Energy Directive’s biomass sustainability requirements and the accompanying Land Use, Land Use Change, and Forestry (LULUCF) Regulation will be the main areas of focus for WWF Hungary. There is additional information about these here.

The 2030 targets adopted by the EU are not in line with the 1.5 degree warming limit, despite the fact that the EU’s climate policy is globally ambitious. It is therefore crucial that future 2040 targets reflect the level of ambition required by science.

The Climate Policy of Hungary

Hungary has passed legislation requiring it to become climate neutral by 2050, in keeping with the pledge made by the European Union. Hungary wants to cut its emissions by at least 40% from 1990 levels under the 2030 sub-target. The base year selection is fortunate because the demise of heavy industries following the regime change resulted in a sizable drop in emissions alone. To achieve the goals, considerably more effort will be required in the upcoming decades. In Hungary, greenhouse gas emissions have typically increased or stagnated between economic booms and busts, declining only during those times. Therefore, it will not be able to meet the established climate protection goals without significant policy changes.

Important economic and social changes are needed to achieve climate neutrality, and interventions must target all areas, not simply industrial output or domestic energy usage. The trends over the past ten years paint a highly diverse picture when looking at how emissions have changed over time in our nation by sector. Transport-related emissions are steadily rising, primarily as a result of the continued increase in the number of vehicles on the road, mostly used, older vehicles that still do not have low emissions. Emissions from buildings have not significantly decreased either. Despite an increase in the number of building energy renovations in all public, commercial, and service sectors, there have been no improvements in the energy efficiency of buildings due to the lack of investment-intensive subsidies and incentives for building users to upgrade. The percentage of imported electricity has increased, while emissions from power generation have dropped. Over the past ten years, emissions from both industry and agriculture have increased as well.

One of the fundamental building blocks for meeting climate targets is a significant increase in the proportion of renewable energy in the energy mix. By European standards, Hungary’s performance in this area is very poor. 14.1% of gross final energy consumption in 2021 was made up of renewable energy, which is significantly less than the EU average of over 40%. The most significant renewable energy source for electricity is solar energy, but since autumn 2022, regulatory decisions have limited its ability to grow. Since 2016, it has been nearly hard to grow wind power capacity; therefore, considerable changes will be required to reach the targets. Solid biomass makes up the majority of renewable energy used in the heating industry, but this high proportion of biomass is about to eliminate the carbon sink capacity required to achieve climate neutrality. Here is more information about biomass utilization and the issues it raises.

The inclusion of the 2050 climate neutrality target in the 2020 law was a significant step toward practical implementation, but it is crucial that the shorter-term sub-targets to accomplish this ambitious goal are also forward-thinking enough to uphold the 1.5 degree global climate target. Unfortunately, there is a considerable difference between the climate goals established by existing international policies and the 1.5 degree trajectory, which indicates that nations will need to be more strict when establishing their own goals, even for 2030.

The National Energy and Climate Plan 2030, the first version of which was finished in 2019, will be reviewed in 2023–2024, providing another chance for practitioners and policy makers to establish more specific and challenging strategic objectives.

In order to effectively cut emissions and prepare for a changing climate, it is crucial to ensure that national climate policy targets are mirrored at the municipal level and to use the subsidiarity principle. Municipal climate strategies (SECAPs), which are addressed in depth by WWF Hungary, are the tools for achieving this. Here is where you may find more details.